This week it is “Walk-to-school” week in the UK. This morning on the way to school my son and I discussed driving to school vs walking to school – which was interesting, although his take on global warming “but then the planet might explode – it’s a good job we’re going on holiday” leaves some room for improvement.

Here is an article I wrote at the same time last year for theWeather magazine of the Royal Meteorological Society.

“This week it is “walk to school week” and “eco-week” at my children’s nursery. So, as well as wearing green and making models out of recycled materials, we’ve been taking the bus in the mornings and walking home in the evenings (well alright, I’ve been walking, the little ones have been riding in the luxury of their double buggy). They love counting the passengers at each bus stop in the morning, and the opportunity to run across a daisy-filled park on the way home. I am discovering muscles I forgot I had! However, it does at least allow me to temporarily ease my guilt at the carbon footprint I have just by being a climate scientist .

Our success at tackling global scale problems such as climate change relies on meaningful and productive collaborations between institutions across the globe. This leaves many climate scientists with a quandary- how to maximise the usefulness of their research whilst minimising their carbon footprint? The development of telephone conferencing via the internet which allows presentations to be shared across many desktops is one possible option. However there is no doubt that a face-to-face meeting at a conference or workshop is often the only way to make progress fast and unambiguous. For example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change holds its work meetings around the globe to allow the inclusion of as many scientists and policy makers from different regions as possible to attend at some point.

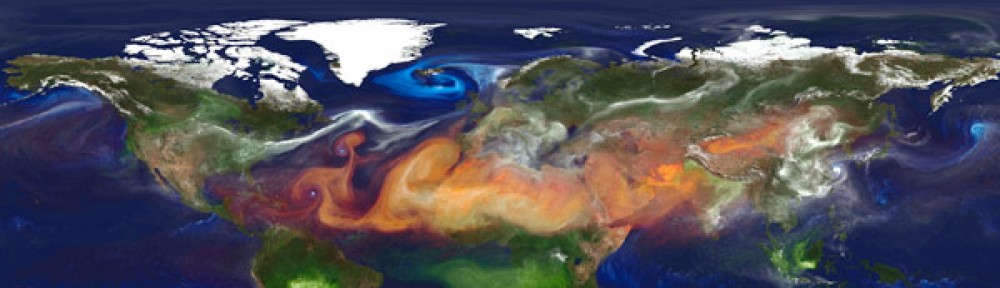

However, the transport sectors are responsible for around 20% of the global CO2 emissions, as well as producing various gaseous and particulate emissions which also contribute to air pollution and climate change. Over the past few years the impact of aviation on climate has received much attention – carbon dioxide emissions, contrails and cirrus cloud that develops from contrails contribute to global warming. This has led many organisations with a climate conscience or a public commitment to reduce carbon emissions to discourage the use of air travel. What received less attention in the media at least is the fact that globally, the greenhouse gas emissions from road traffic produces several times the change to the energy balance of the earth (leading to climate change) as global air travel. The energy change due to particles is also substantially larger for road traffic as these aerosols absorb solar radiation and generally warm up the atmosphere. The effects of maritime shipping receives some press in the guise of the “food miles” debate, but its overall effect on global temperature is probably to cool it since high sulphur content fuel results in more sulphate aerosols which scatter solar radiation away from the surface. Reducing the sulphur content in shipping fuel (desirable from an air pollution standpoint) may actually exacerbate global warming slightly.

Some scientists subscribe to carbon offset schemes either privately or more publicly, but the choice of off-set mechanism requires careful thought – not all schemes are equal in effectiveness or scientific value. Additionally, some of my group’s research relies on flying on research aircraft – potentially contributing to the particles that they are measuring (obviously we don’t fly around measuring our own emissions directly!). This has always seemed like something of a contradiction to me (and many others, see for example Kevin Andersons blog and this one.. ) . Striking a balance between travel that makes our research more effective, efficient and scientifically sound and minimising our impact on the environment is a considerable challenge, but should be applied to everyday car driving as well as flying). At least I’ll have something to ponder as I push the buggy up the hill towards home.”

Note that references to scientific journals were not included in the original article due to it’s intended audience, but details can be found in the following papers.

Balkanski, Y., Gunnar Myhre, Michael Gauss, G. Rädel, E Highwood and Keith P. Shine, 2010. Direct radiative effect of aerosols emitted by transport: From road, shipping, and aviation. Atmos. Chem. Phys., 10: pp. 4477-4489.

Skeie, Ragnhild Bieltvedt, Jan S. Fuglestvedt, Terje Berntsen, Marianne Tronstad Lund, Gunnar Myhre and Kristin Rypdal, 2009. Global temperature change from the transport sectors: Historical development and future scenarios. Atmospheric Environment, 43 (39): pp. 6260-6270.

Fuglestvedt, Jan S., Terje Berntsen, Gunnar Myhre, Kristin Rypdal and Ragnhild Bieltvedt Skeie, 2008. Climate forcing from the Transport Sectors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), vol 105 (no. 2): pp. 454-458.