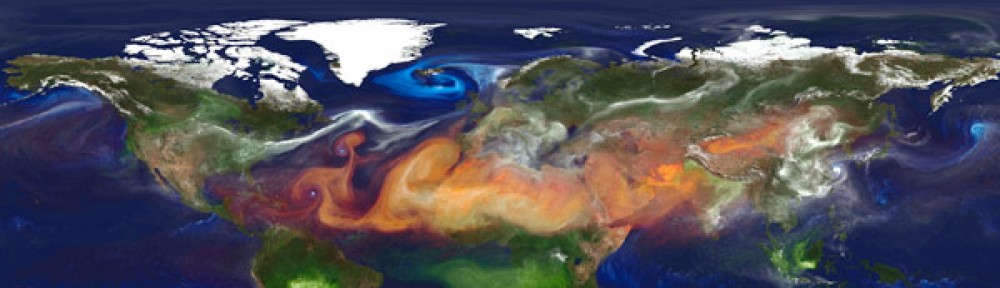

I am feeling envious. Envious of those researchers, or research leaders, who have found a particular niche area, and who are able to spend the majority of their time there. I am at a project meeting for one of the 4 projects I am involved in at the moment. It so happens that the work my group does at the moment concerns 3 distinct geographical regions: the Sahara, the Brazilian rainforest and the South Asian monsoon. In each case, my interest is in the role that aerosol could play in driving regional weather and climate, but in each case the background is very different. On days like today, I am having to catch up with the basics of biomass burning and all the previous literature before I am even on the same page as those who are working more continuously on one area.

It ultimately comes down to the old breadth versus depth argument. Ever since I started winning research funds I have always had quite a few different strands of research on the go at any one time. This is interesting and exciting, but can be exhausting to keep up with. At one point I had people or myself working on 7 different topics. I felt like I was constantly behind on all fronts, although all projects were interesting. In the end, I breathed a sigh of relief when one or two of the projects ended. For me, breadth has worked so far, but at moments of low self-confidence I sometimes wonder whether the broad approach that I sort of fell into (possibly related to inability to say no?) was the right decision.

Breadth versus depth is an age-old discussion at all levels of education, in all fields. To me it seems necessary to have some degree of flexibility in terms of research area since the very process of doing research opens up new questions, and more pragmatically, sometimes funding is easier to come by in some areas than others. Again, opinions amongst colleagues are divided between those who “chase” funding, and those who stick to a narrow area even if it means research grants are hard to come by (not all institutions will be totally happy about this given the way research funding is used as a metric). Most of us are somewhere in between. This variation regarding the importance of breadth vs depth has unfortunately reared its heard in discussions of potential academic hires – in one case that I was witness to a long time ago, the breadth appeared to be valued differently depending on whether the candidate was male or female – in the case of the male, breadth was viewed as positive and creative – in the case of the female it was discussed as “lack of focus” etc. Not our finest hour…

It’s a question that I get asked by postdocs and more junior academics very frequently, not just in terms of research area, but also the balance between research, teaching experience and other academic activities. It’s also something that varies between graduate programmes in different countries , as discussed in this article by Robert A. Segal for Times Higher Education. My usual response is to say that it varies and point to examples from within our department of those who are incredibly narrowly focused, and those with a broader portfolio. There is success in both cases (but then everyone’s definition of success is different too!).

When I was a junior lecturer, my line manager at the time Prof Alan Thorpe, now Director of the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting, asked me to draw a map linking my various current research projects together and to identify 2 to 3 common science questions or themes. Then, each time a new opportunity presented itself, I was to use this to consider whether it was either central to one of my themes, or developing a new theme that I had in mind to expand at the expense of something else. At the time it was useful in clarifying that there were some universal themes across all 7 projects. For a few years it was helpful in giving me a reason to say “no” to some requests. I periodically review and revise this map of my strategy and still find it a useful process. I don’t think its giving too much away to show the version as at 2012 with the projects that were running then. I still have lots of things going on, but can see that at that point there was more emphasis on modelling than work with observations – perhaps a reflection of being a parent and not wanting to go away on fieldwork quite so much. Looking back at earlier versions its interesting to see how some things have evolved (the balance of modelling vs fieldwork whilst other aspects have remained more constant (the use of idealised experiments to understand processes). I wonder what future versions will look like?