As you may have noticed, this blog hasn’t had many posts for a long time. In 2019 I left my academic post at the University of Reading in order to pursue new challenges. I now run my own businesses, Equasense (a diversity and inclusion consultancy) and SendThemSoaring (where I coach academics, researchers and scientists on career and personal development). Mostly I write blogs over on those sites these days, but I am keeping this one alive because: a) it’s got my crochet global warming blanket on it, b) it’s good to remember my former career of which I am very proud, and c) I may come back to writing more about general reflections here one day.

Crocheting together – an example of social learning

My most popular blog to date has been on the combination of crochet and climate change data, but crochet is relevant to the teaching and learning side of my working world too. Having taken part in a variety of Crochet ALongs (CALs) in recent years, and having interest in the broader issue of social learning as educationalists, Professor Shirley Williams and I reflect here on the history of craft-alongs, and their place in the evolution of learning towards becoming more informal and more social.

Crochet’s resurgence

Crochet has undergone a revival recently, especially in relation to the benefits of crochet (and knitting) for relaxation. There are even books and articles on mindful crochet and crochet therapy. However, there is no clear evidence of the origins of crochet (Marks, 1997), although there are a number of theories of origins ranging through developments in Arabia, China to South America. Certainly crochet came to popularity in Europe during the nineteenth century, Potter (1955) cites Caulfeild and Saward’s “Dictionary of Needlework” dating its popularity to 1838, with even Queen Victoria crocheting (Canadian War Museum, n.d.).

One of eight scarves Queen Victoria crocheted for presentation to members of her forces fighting in South Africa. This is the scarf awarded to Private R.R. Thompson on display at the Canadian War Museum. Photo from Canadian War Museum Ottowa

Developments in various countries have led to different ways of identifying hook sizes, and to multiple names for the same stitch, including some terms used in both US and UK crochet referring to different stitches. There is no worldwide standard for abbreviations of crochet terms and corresponding symbols (Hazell, 2013). Thus the world of crochet has its own terminology and “jargon” that needs explanation to the beginner similar to academic disciplines, and perhaps lends itself particularly well to social learning.

Crafters, the internet and the birth of online Craft-alongs

A Craft-along is a group of crafters working, initially simultaneously, on their own realization of the same piece of work. Facilitated by the internet, participants work together on their own instantiation of an artifact (such as a crochet blanket), following instructions available online and sharing their experiences across an Internet platform such as Facebook, many participations start as soon as an along is launched, but completion times vary. Craft-alongs are usually called by the name of the craft involved; crocheters join crochet alongs (CALs), while knitters join knit alongs (KAL).

In fact, crafters in general were early adopters of the Internet, establishing and using Usenet groups, with lists such as alt.sewing and rec.crafts.textiles in the early 1990s (Rheingold, 2000). In 1998 a book was published “Free Stuff for Quilters on the Internet” (Heim & Hansen, 1998) and subsequently revised in a second and third edition, variants of the books were produced for other crafts (for example a version for a range of needlecrafts (Heim, 2003)). By 1998 it is reported quilters were using the Internet to collaborate on designs (Williamson, Glassner, McLaughlin, Chase, & Smith, 1998), while the Knitting Bloggers NetRing was established in early 2002 (Wei, 2004). Kucirkova and Littleton (2015) use the term “Community-Oriented Digital Learning Hub” (DLH) to describe online communities such as the yarn based Internet site Ravelry (Humphreys, 2009; Ravelry, n.d.) where members share their guides and patterns (“how to guides”) before and after the production of the artifact, and the community can “like”, comment and develop supplementary materials.

Many of these communities are examples of technology-enabled communities of practice (Le Deuff, 2010; Wenger, White, & Smith, 2009) using varied Internet-based resources and products as the home for individual communities; these technologies have changed considerably over recent years and some of the products used by early communities are no longer available (Wenger, 2001; Wenger et al., 2009). In one of the few texts combining craft and the digital world, Gauntlett (2011) suggests both that: Web2.0 offers a platform on which to share creative artifacts, and that creative projects are invaluable for human happiness.

Within the literature Brown and Brown (2011) dated the emergence of the term “knit along” to 2003/4:

“The term knitalong emerged out of the Internet knitting culture of blogs and discussion groups around 2003 and 2004, when it was used most often to describe the practice of knitters in different place working on the same project during the same time period.” (page 7)

While Wei (2004) identified the term as in use by bloggers in the period 2002/3. The emergence of the term in relation to other crafts is not possible to establish from the literature, but within social media hashtags including quiltalong, knitalong, crochetalong are now in widespread use.

We should also note that some people (Brown & Brown, 2011) use the term knitalong to refer to events which are purely physical, such as meetings of knitting groups in cafes and pubs; elsewhere (Minahan & Wolfram Cox, 2006) the term stitch’n bitch is used to describe physical and virtual groups in which knitters exchange ideas, resources and chat, while other authors (Kelly, 2014) use this term for only physical groups. The term stitch’n bitch was used as a title for a book (Stoller, 2003), some credit this as the origin of the term (Minahan & Wolfram Cox, 2006), however the use of the term pre-dates the book, for example Castleton (1990) mentions:

“…a monthly “Stitch ‘n Bitch” get-together with friends…” (page 95),

but the term became more widely use after Stoller’s book was published. However, we focus on internet based alongs in our consideration of the social learning aspects.

Crochet alongs as mass social learning.

Completed Dances on the Beach CAL involving learning several different types of stitches. Completed by Ellie Highwood, 2017

At any one time there are many “alongs” in various stages of maturity on the internet. Ravelry (Humphreys, 2009; Ravelery, n.d.) lists over 2500 Alongs (562 of which are classified as active), with 1484 knitalongs (467 active), 302 crochetalongs (95 active), and a small numbers of other crafts. A study in 2012 (Orton-Johnson, 2014) noted that amongst respondents each belonged to an average of 2 CALs on Ravelry. The closed Facebook group: CAL – Crochet A Long (n.d.) has some 45,000 members and lists about one new CAL a month, each with hundreds or a few thousand “guests” registered, many of these CALs also have a presence elsewhere on the Internet. This group serves as a focus allowing people to continue following CALs, and crucially learning from the CAL, outside the official time period. At any one time, people on this group are working on both current CALs and those from several years ago.

Learning takes place usually after provision of initial material (pattern) which is sometimes released in sections, and usually involving the course initiator(s), and a much larger group of participants. Learning includes not only the techniques and terminology, but colour combinations and yarn choice. Participants often provide translations of patterns (officially sanctioned or otherwise), and some provide videos of particularly challenging sections. Very rapidly, learning and teaching is spread across a vast group of participants.

Interestingly, this type of relatively informal, social, learning also occurs in Massive Open Online Courses (or MOOCs) which cover a wide range of subjects, and usually involve awareness raising, knowledge and skill transfer, but rarely involve the production of a physical artefact. CALs and MOOCs share some characteristics, but also can learn from each other. We are writing a more academic comparison of crochet-alongs and MOOCs for publication in a social learning journal.

References

Brown, L., & Brown, M. J. (2011). Knitalong: Celebrating the tradition of knitting together: Open Road Media.

CAL – Crochet A Long. (n.d.). Facebook [Group]. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/groups/668646249929007/

Canadian War Museum. (n.d.). Canada & The South African War, 1899-1902 : The Queen’s Scarf of Honour. Retrieved from http://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/boer/queensscarf_e.shtml

Castleton, A. (1990). Speaking out on domestic violence. Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 23, 108-115. Gauntlett, D. (2011). Making is connecting: Polity Press.

Hazell, S. (2013). 200 Crochet Stitches: Search Press.

Heim, J. (2003). The Needlecrafter’s Computer Companion: Hundreds of Easy Ways to Use Your Computer for Sewing, Quilting, Crossstich, Knitting, And More! : No Starch Press.

Heim, J., & Hansen, G. (1998). Free Stuff for Quilters on the Internet: C & T Publishing.

Humphreys, S. (2009). The economies within an online social network market: A case study of Ravelry.

Kelly, M. (2014). Knitting as a feminist project? Paper presented at the Women’s Studies International Forum.

Kucirkova, N., & Littleton, K. (2015). Digital learning hubs: theoretical and practical ideas for innovating massive open online courses. Learning, Media and Technology, 1-7. doi:10.1080/17439884.2015.1054835

Le Deuff, O. (2010). Réseaux de loisirs créatifs et nouveaux modes d’apprentissage. Distances et savoirs, 8(4), 601-621.

Marks, R. (1997). History of Crochet. Chain Link Newsletter, reproduced at http://www.crochet.org/?page=CrochetHistory

Minahan, S., & Wolfram Cox, J. (2006). Making up (for) society? Stitch, bitch and organisation. Paper presented at the ANZAM 2006: Proceedings of the 20th Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management Conference.

Orton-Johnson, K. (2014). Knit, purl and upload: new technologies, digital mediations and the experience of leisure. Leisure Studies, 33(3), 305-321.

Potter, E. (1955). English Knitting and Crochet Books of the Nineteenth Century. The Library, 5(1), 25-40.

Stoller, D. (2003). Stitch’n bitch: The knitter’s handbook: Workman Publishing.

Wei, C. (2004). Formation of norms in a blog community.

Wenger, E. (2001). Supporting communities of practice. Retrieved from https://guard.canberra.edu.au/opus/copyright_register/repository/53/153/01_03_CP_technology_survey_v3.pdf

Wenger, E., White, N., & Smith, J. D. (2009). Digital habitats: Stewarding technology for communities: CPsquare.

Williamson, M. B., Glassner, A., McLaughlin, M., Chase, C., & Smith, M. (1998). Constructing community in cyberspace. Paper presented at the CHI 98 Conference Summary on Human Factors in Computing Systems

On Not “moving on”

On Monday I received recognition of 21 years service as an employee of the University of Reading (I’ve actually been here for 24 years but 3 as a PhD student don’t count!). In that time I have gone from postdoc to Professor, held many teaching and learning administrative roles, been Head of Department of Meteorology and moved into a University wide leadership role. I get invitations to speak at international meetings, to review funding proposals and appointments from across the globe. I have published a reasonable number of papers and won a considerable amount of funding. PhD students have graduated and gone on to roles in other research organisations and BEIS. I am President of the Royal Meteorological Society. I don’t feel that I have done anything particularly amazing other than working averagely smartly and being pro-active in terms of my own career development.

On Monday I received recognition of 21 years service as an employee of the University of Reading (I’ve actually been here for 24 years but 3 as a PhD student don’t count!). In that time I have gone from postdoc to Professor, held many teaching and learning administrative roles, been Head of Department of Meteorology and moved into a University wide leadership role. I get invitations to speak at international meetings, to review funding proposals and appointments from across the globe. I have published a reasonable number of papers and won a considerable amount of funding. PhD students have graduated and gone on to roles in other research organisations and BEIS. I am President of the Royal Meteorological Society. I don’t feel that I have done anything particularly amazing other than working averagely smartly and being pro-active in terms of my own career development.

But, there are a significant number of my colleagues both near and far who think this career path should have been impossible. Here you might expect me to mention being female and working part-time for the past 10 years. And I will – because these are definitely viewed as “unusual identities” for successful academics in at least some places. But these are not in fact the main reason that some colleagues might think that I should not be where I am today. It is instead exactly what was recognised by the University this week. I HAVE NOT MOVED INSTITUTION.

I should not be where I am today. It is instead exactly what was recognised by the University this week. I HAVE NOT MOVED INSTITUTION.

Recently I have noticed an increasing prevalence of expression of the belief that it is a requirement to move institution in order to demonstrate independence as a researcher, a necessary step in gaining an academic position. Perhaps this has always been one pervasively held view, indeed I have been told this on occasion regarding myself (fortunately not by the wonderfully open-minded people who hired me and kept me here). In some countries this is enshrined in the career path system, so determined are they that external perspectives need to be gathered in this way. What is upsetting is that I am increasingly seeing this feedback given to really strong Early Career Researchers as they apply for independent research fellowships from a variety of funding sources. Even though some of the funding agencies in my area state to reviewers that applicants should not be penalised for not moving around, I have seen paragraphs of feedback doing exactly this given to applicants, regardless of any recognition that the chosen institution is one of the best places for the science that needs to be done. I understand that applicants should be expected to justify the choice of institution to which they are applying. I don’t have a problem with reviewers giving feedback on whether the choice of institution makes sense on science grounds. But I DO have a problem with the assumption that unless you have moved around, you cannot be a bona-fide independent academic. From another perspective, as a Head of Department it can be incredibly frustrating to have valued team members who want to stay but you struggle to keep because of these quite pervasive opinions.

I did not stay at Reading for any “personal” reasons, at least not for the first 11 years of my career here. I stayed at Reading because it is one of the best places in the world to do meteorological research. End of. Yes, I can appreciate the value of different perspectives and experiences that might be brought by working in different institutions. However, this can be gained by different means – for examples visiting other institutions, building collaborations with overseas teams. Additionally, moving has quite a large overhead in terms of setting up a new group and integrating into a new environment both at work and at home – I have mentored and coached several people through these transitions both here and elsewhere. It is common for there to be a gap in publications following such a move due to these overheads, and this has to be balanced against the “independence” shown by moving your life around. The positive productivity benefit of knowing the environment and having a support network in place seems to be less appreciated.

Of course I am biased since I have not moved around. Others will be biased towards demanding that postdocs move around because they have moved around – I guess to them folks like me are the exception that prove the rule! Ultimately, if people want to move around or feel that they need to do so to achieve what they want to achieve then great. However, I’d like to end with a couple of requests.

Firstly, to funding awarders – if a review comes back full of statements about whether the applicant has moved around or not that are not directly related to whether the science can be done in the chosen location, please disregard this, and think about whether it should be passed on to the applicant. The reviewers are, after all, at least where explicitly told not to penalise for this, giving the impression that they are ignoring your instructions. This damages your reputations as inclusive organisations. Appearing to take into account demands that applicants move could in fact be discriminating against certain communities whose equal opportunities are protected under the UK Equality Act 2010.

Secondly, to fellowship application reviewers. Please put to one side those limiting beliefs that we all hold, and judge the applications on the science and on the capacity of the applicant to do science in the chosen location, not whether the applicant has moved around. There may be many reasons why people haven’t moved around, including caring responsibilities, financial constraints, disability or mental health issues. People may not wish to declare these.

Or it could just be, as it was for early-career me, that they are already in the best place to do the science that needs to be done.

With a huge thanks to those who have made it a wonderfully challenging yet productive and happy 21 years at Reading.

Deadlines

Deadlines – often a necessary step to move things forward, but we need to talk about unnecessarily short windows of opportunities over traditional holiday and family times, and deadlines that implicitly encourage working through weekends. Of course there are some unavoidable short deadlines or deadlines constrained to a particular date, but here I refer to those deadlines where these is no particular time critical aspect. Short windows over traditional holiday times, particularly discriminate against those with caring responsibilities, especially those with school age children who are forced to take holiday actually LOOKING AFTER children during the school holidays. Whilst by no means exclusively affecting women, this may particularly discriminate against women, and against staff in certain age groups. Deadlines that seemingly encourage working over weekends or outside normal working hours are potentially more broadly damaging at a time when mental ill health is on the increase amongst University staff.

Some examples of, in my opinion, poor practice, include:

- an internal deadline for research proposals on the day that University and Schools return after Christmas. Whilst I know that these are set themselves relative to research council deadlines, in reality it means one of two things. Either you plan to get it done before the Christmas break (our University shuts down entirely between Christmas and New Year, and obviously some of us need to look after children during the School holidays even if that were not the case), or, you will be working over the Christmas break, squeezing in writing and editing around family or other commitments, and missing out on a chance for even the shortest of breaks. Some people will say the former is impossible due to teaching commitments. If your proposal involves multiple collaborators the latter becomes way more likely. There is of course a 3rd option, to decide not to apply, but this is a bold move given pressure to bring in funding.

- A similar internal deadline for internal promotion cases – given the relative under-representation of women in the professoriate, it is unfortunate that I know of several women for whom Christmas family responsibilities preclude working on promotion cases. There are doubtless men for whom this is also true, but I have not heard them speak about it explicitly.

- A research Council deadline for funding applications with the online application system only open for two weeks at the end of August. Despite notice being given, this short period of accessibility to the submission system discriminates against those forced to take holiday in the school holidays – the proximity to the bank holiday also makes this a popular holiday choice for many others. Holidays are often arranged a long time in advance and cannot be rearranged easily.

- A research council deadline for applicants to respond to the reviewers’ comments on their proposal, originally timetabled for the whole of August but subsequently narrowed to one week at the end including the bank holiday – similar problems to the preceding example – and interesting justified on the basis of needing to give the final panel at least two weekends to look at the papers (possible multiple problems here – but at least there is presumably a week in between the weekends!)

- Papers appearing at 4 pm for a 9.30 am meeting the following day OR at 4 pm on a Friday for a 9.30 am meeting on the immediately following Monday morning is also fairly unacceptable since it likely requires people to work in the evening or over the weekend or attend the meeting unprepared – a waste of time for everyone. For me working part-time, finishing at 3 on Fridays to do the school run – it guarantees I will not read them and therefore will not be able to contribute effectively to the meeting. Not exactly inclusive practice to enable diverse voices to be heard.

I am delighted to report that once attention was drawn to occurrence 4 above, positive changes were made. An email from one of the applicants resulted in an extension of the response period back towards the original plan, with reviewers’ comments being delivered as soon as they were received. In the case of 3, a solution is also under discussion. This willingness to reflect and react when the potential problems are pointed out is admirable and should be recognised. However, consider how much better it would be if organisations looked at their deadline setting through an inclusive lens from the get go.

Of course, no deadline will ever please everyone. But, there are perhaps some more obvious things to avoid:

- Short windows of opportunity in August (admittedly England-centric view)

- Deadlines immediately following significant national holiday periods

- Deadlines on Mondays

If deadlines are justified on the basis of timescales need to complete process, then either lengthen or shift the entire process, or perhaps preferably, consider whether you can simplify and reduce the process or paperwork to speed things up.

And if you want me to contribute in an informed way to a meeting, I need papers at least 2 working days in advance!

#climatechangecrochet – The global warming blanket.

Q. What do you get when you cross crochet and climate science?

A. A lot of attention on Twitter.

At the weekend I like to crochet. Last weekend I finished my latest project and posted the picture on Twitter. And then had to turn the notifications off because it all went a bit noisy. The picture of my “global warming blanket” rapidly became my top tweet ever, with more retweets and likes than anything else. Apparently I had found a creative way to visualise trends in global mean temperature. I particularly liked the “this is the most frightening knitwear I have seen all year” comment. Given the interest on Twitter I thought I had better answer a few of the questions in this blog. Also, it would be great if global warming blankets appeared all over the world.

How did you get the idea?

The global warming blanket was based on “temperature” blankets made by crocheters around the world. Their blankets consist of one row, or square, of crochet each day, coloured according to the temperature at their location . They look amazing and show both the annual cycle and day-to-day variability. Other people make “sky” blankets where the colours are based on the sky colour of the day – this results in a more muted grey-blue-white colour palette. UPDATE – IN 2022 I became aware that a global temperature blanket had been produced by Joan E Sheldon, an estaurine scientist and weaver in 2015 and a pattern made available on Ravelry in 2017. I had not seen this when I made my blanket, but I always thought there would likely be others out there in the textiles world. If you are here looking for the first “climate stripes” manifestation, it would be hers. )

I wondered what the global temperature series would look like as a blanket. Also, global warming is often explained as greenhouse gases acting like a blanket, trapping infrared radiation and keeping the Earth warm. So that seemed like an interesting link. I also had done several rainbow themed blankets in the past and had a lot of yarn left that needed using.

Where did the data come from?

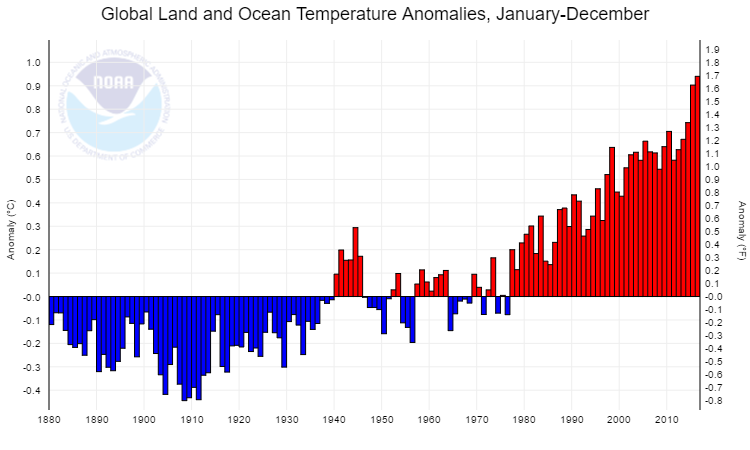

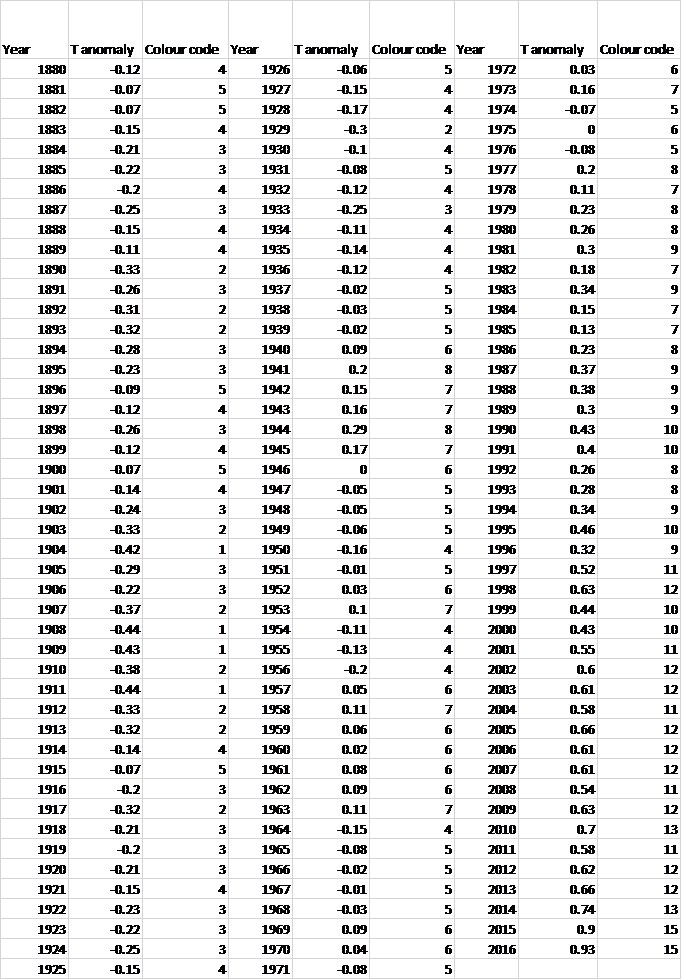

I used the annual and global mean temperature anomaly compared to 1900-2000 mean as a reference period as available from NOAA https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/time-series/global/globe/land_ocean/ytd/12/1880-2016. This is what the data looks like shown more conventionally.

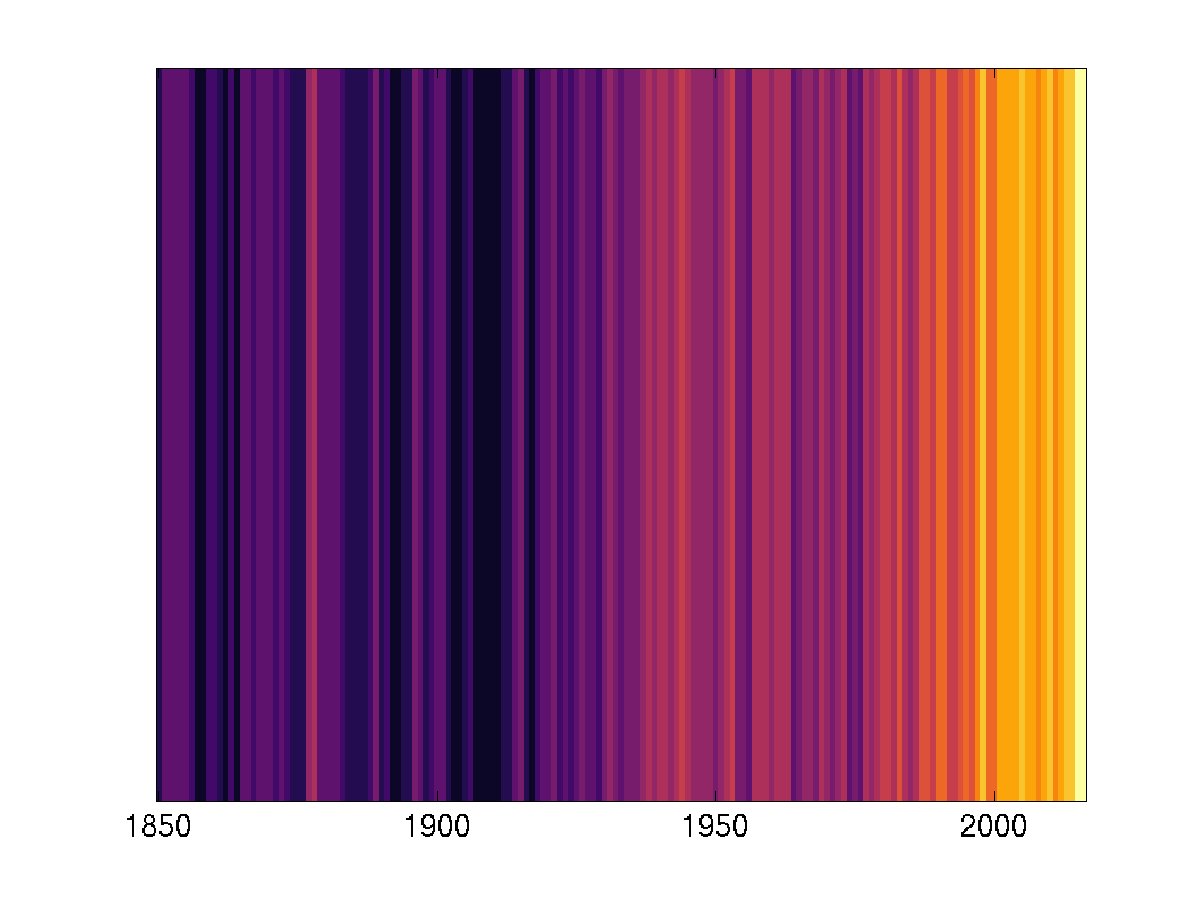

I then devised a colour scale using 15 different colours each representing a 0.1 °C data bin. So everything between 0 and 0.099 was in one colour for example. Making a code for these colours, the time series can be rewritten as in the table below. It is up to the creator to then choose the colours to match this scale, and indeed which years to include. I was making a baby sized blanket so chose the last 100 years, 1916-2016.

1929 1940-46 1954-56 1991/2 1997/8

If you look closely you can see the 1997-1998 El Nino (relatively warm yellow stripe), 1991/92 Pinatubo eruption (relatively cool pink year) as well as cool periods 1929, and 1954-56 and the relatively warm 1940-46. Remember that these are global temperature anomalies and may not match your own personal experience at a given location!

Because of these choices, and the long reference period, much of the blanket has relatively muted colour differences that tend to emphasise the last 20 years or so. There are other data sets available, and other reference periods and it would be interesting to see what they looked like. Also the colours I used were determined mainly by what I had available; if I were to do another one, I might change a few around (dark pink looks too much like red in the photograph and needed a darker blue instead of purple for the coldest colour), or even use a completely different colour palette – especially as rainbow colour scales aren’t great as they can distort data and render it meaningless if you are colour blind Ed Hawkins kindly provided me with a more user friendly colour scale which I love and may well turn into a scarf for myself (much quicker than a blanket!).

How can I recreate this?

If you want to create something similar, you will need 15 different colours if you want to do the whole 1880-2016 period. You will need relatively more yarn in colours 3-7 than other colours (if, like me you are using your stash). You can use any stitch or pattern but since you want the colour changes to be the focus of the blanket, I would choose something relatively simple. I used rows of treble crochet (UK terms) and my 100 years ended up being about 90 cm by 110 cm. You can of course choose any width you like for your blanket, or make a scarf by doing a much shorter foundation row. It goes without saying that it could also be knitted. Or painted. Or woven. Or, whatever your particular craft is.

How long did it take?

I used a very simple stitch, so for a blanket this size, it was a couple of months (note I only crochet in the evenings 2 or 3 evenings a week for a couple of hours with more at some weekends). It helped that the Champions League was on during this time as other members of the household were happy to sit around watching football whilst I crocheted. Weave the ends in as you go. There are a lot of them, and I had to do them all at the end. The time flies because….

Why do I crochet?

I like crochet because you can do simple projects whilst thinking about other things, watching TV or listening to podcasts, or, you can do more complicated things which require your full attention and divert your brain from all other things. There is also something meditative about crochet, as has been discussed here (https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/may/16/knitting-yoga-perfect-bedfellows) I find it a good way to destress. Additionally, a lot of what I make is for gifts or for charities and that is a really good feeling.

What’s next?

Suggestions have come in for other time series blankets e.g. greys for aerosol optical depth punctuated by red for volcanic eruptions, oranges and yellows punctuated by black for solar cycle (black being high sun spot years), a central England temperature record. Blankets take time, but scarves could be quicker so I might test a few of these ideas out over the next few months. Would love to hear and see more ideas, or perhaps we could organise a mass “global warming blanket” make-athon around the world and then donate them to communities in need.

And finally.

More seriously, whilst lots of the initial comments on Twitter were from climate scientists, there are also a lot from a far more diverse set of folks. I think this is a good example of how if we want to reach out, we need to explore different ways of doing so. There are only so many people who respond to graphs and charts. And if we can find something we are passionate about as a way of doing it, then all the better.

Three women meteorologists for International Women’s Day 2017

On International Women’s Day 2017 I could write about famous women that lots of people (although still not enough) already know about. I could write honouring the wonderful women in my life, but other social media platforms are the way to do that. Instead I would like to introduce you to three influential voices of women in Meteorology, recognising my multiple work roles as a climate scientist, President of the Royal Meteorological Society and Dean for Diversity and Inclusion. Forgive the length of the post, there is so much to say about each!

Eunice Foote (1819-1888) was both a scientist and a proponent of women’s rights. As has come to light over only the past few years (work by Sorenson in 2011, and more recently Katherine Hayhoe), Foote conducted early work on what we now call the greenhouse effect. The experiments investigated the warming effect of the sun on air, including how this was increased by carbonic acid gas (carbon dioxide), and bear a striking resemblance to some outreach experiments still used today. She also speculated on how an atmosphere of this gas might affect climate. “An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature from its own action as well as from increased weight must have necessarily resulted.”

Her paper “Circumstances affecting the heat of the sun’s rays,” was presented by Prof. Joseph Henry at the American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in 1856, three years before Irish scientist John Tyndall started working on the gas. Interestingly, a contemporary account describes the occasion as follows: “Prof. Henry then read a paper by Mrs. Eunice Foote, prefacing it with a few words, to the effect that science was of no country and of no sex. The sphere of woman embraces not only the beautiful and the useful, but the true.”

Eunice was a member of the editorial committee for the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the first women’s rights convention to be organized by women, and one of the 68 women and 32 men who signed the convention’s Declaration of Sentiments. One of the opening paragraphs of this declaration, based on the Declaration of independence reads:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their powers from the consent of the governed. Whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these rights, it is the right of those who suffer from it to refuse allegiance to it, and to insist upon the institution of a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness”

And it concludes:

“In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object.”

This strikes me as still relevant to both Equality and climate change work today.

Eleanor Ormerod (1828-1901) was the first woman to be made a Fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society. Passionate about insects from childhood, she became an authority on “Injurious insects and Farm Pests”. Her works was honoured in time by Royal Horticultural Society who awarded her the Flora medal, the Royal Agricultural Society who appointed her as consulting entomologist, the University of Moscow from whom she received silver and gold medals from the University of Moscow for her models of insects injurious to plants and the Société nationale d’acclimatation de France who awarded her a silver medal.

Eleanor often tested out the effect of insects on herself, for example:

“Miss Ormerod, to personally test the effect, pressed part of the back and tail of a live Crested Newt between the teeth.”The first effect was a bitter astringent feeling in the mouth, with irritation of the upper part of the throat, numbing of the teeth more immediately holding the animal, and in about a minute from the first touch of the newt a strong flow of saliva. This was accompanied by much foam and violent spasmodic action, approaching convulsions, but entirely confined to the mouth itself. The experiment was immediately followed by headache lasting for some hours, general discomfort of the system, and half an hour after by slight shivering fits.” –Gadow, 1909

Eleanor’s link with meteorology came via her brother, much of her interest being in the relationship of weather to insects. She compiled and analyzed weather data extensively, and published in the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. I chose Eleanor because of the link between entomology, my late father’s field, and meteorology, mine. In addition, she is said to have been the inspiration for Gaskells heroine in Wives and Daughters and for a short story by Virginia Woolf; an excellent cross-over between science and literature.

(Gadow, Hans 1909. Amphibia and Reptiles. Macmillan and Co. London.)

Joanne Simpson (1923-2010) was the first female meteorologist with a Ph.D. Fascinated by clouds as a child, she might well have gone into astrophysics were it not for the intervention of World War II. As a trainee pilot she had to study meteorology and after getting her training from Carl Gustaf Rossby’s new World War II meteorology programme, spent the war years teaching meteorology to Aviation cadets. Her PhD work focussed on clouds, then regarded as not a particularly important part of the subject, but her early research based revealed cloud patterns from maps drawn from films taken on tropical flights. Subsequently she went on to show how tropical “hot tower” clouds actually drive the tropical circulation, and to propose a new process by which hurricanes maintain their “warm core”.

Following stints at UCLA, NOAA and the University of Virginia, Joanne ended up at NASA Goddard Space Flight Centre where for the first time she met other women meteorologists. It was here that she made what she described as the single biggest accomplishment in her career. She was asked to lead the “study” science team for the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) – a satellite carrying the first space-based rain radar. Working with project engineers and recruiting many scientists, Joanne worked on TRMM from 1986 until its launch in 1997. TRMM has led to many discoveries about tropical rainfall, including in 2002 the ability to estimate latent heat in the tropics. This work linked directly back to Joanne’s early work on tropical cloud processes.

Rightly recognised, Joanne was granted membership to the National Academy of Engineering, awarded the Carl-Gustaf Rossby Award (the highest honor bestowed by the American Meteorological Society), presented with a Guggenheim Fellowship. I chose Joanne because she served as President of the American Meteorological Society, as I am serving as President of the Royal Meteorological Society this year. You can read much more about Joanne Simpson in this excellent portrait at NASA.

Scientist? Brilliant? Masculine?

Today the news has been full of a study in the USA which reported that girls as young as 6 or 7 start to remove themselves from challenges associated with being “really really smart”. The research, by Lin Bian, Sarah-Jane Leslie and Andrew Cimpian of the Universities of Illinois, New York University and Princeton found that around the ages of 6-7, there started to emerge a difference in the way boys and girls viewed being “really really smart” in relation to their own gender.

Today the news has been full of a study in the USA which reported that girls as young as 6 or 7 start to remove themselves from challenges associated with being “really really smart”. The research, by Lin Bian, Sarah-Jane Leslie and Andrew Cimpian of the Universities of Illinois, New York University and Princeton found that around the ages of 6-7, there started to emerge a difference in the way boys and girls viewed being “really really smart” in relation to their own gender.

Wanting to explore the origin of the widespread “brilliance = male” stereotype that has been used to explain the lack of women in many occupations including science and engineering, and been demonstrated in reference writing, (more studies), they used younger participants than previous studies. Over 4 different studies they discovered that 5 year olds were equally likely to rate members of their own gender as being brilliant, but that by age 6-7, girls were statistically significantly less likely to rate members of their own gender as brilliant. A corresponding question about rating pictures of people as ” really really nice” started to reveal the opposite stereotype about women being nicer than men. The older children in the study also started to dissociate high school marks with “being clever” – they identified that girls got better marks in class than boys but did not associate this with girls being clever. (Actually the rest of us could probably learn something from this- some of the cleverest people I know would not “look” clever on paper as they may have finished formal education early and learnt in other ways – too often smart= good marks).

So these studies showed that children are influenced by gender stereotypes in relation to brilliance and niceness sufficiently such that they start to show these stereotypes around the ages of 6-7 (it should be noted that this study included mainly middle-class children of whom 75% were white, therefore it would be interesting to see how the conclusions differ across different cohorts). But it also showed some evidence that it influences choices made. Given a choice of two games, one presented as for those who work really hard, and one for those who are really really smart, both genders showed similar interest in the “try hard” game at all ages, but girls showed significantly less interest in the “really smart” game at ages 6 and 7.

In order to tell if these results actually have an influence on career paths, we would need to complete a longitudinal study of many many children and their influences. One such study is underway as part of the ASPIRES project run from Professor Louise Archer’s team at Kings College London. Whilst we wait for the second phase of that study to take us all the way from 10-18, we can perhaps start to piece together the new work with even younger children.

The ASPIRES work with 10-14 year olds suggests that children of this age and their parents strongly associate science with masculinity and science with cleverness. Whilst girls claim to enjoy science, they can’t see themselves in science careers. Those girls who are defined as “science keen” either by themselves or others often struggle to combine this interest with other stereotypical views of femininity or “girliness” – needing to engage in “identity work” to feel comfortable with their choices. “Science-keen” girls in the Archer et al (2012,2013) studies come in two flavours – those who also excel in other areas, e.g. sport, music etc and take pains to emphasise their “roundedness” and those who adopt the “blue-stocking” or nerdy approach. All the science-keen girls in this study were middle-class.

There are many many studies of how stereotype threat affects college-age students and beyond, brilliantly collected in “Whistling Vivaldi” which broadens the discussion from gender to other characteristics such as race and ethnicity – or indeed the i ntersectionality of gender and race. A highly recommended read for evidence based studies over a range of conditions and subject areas, you can hear Claude Steele talk about how he came to write the book, or watch a longer Claude Steele lecture.

ntersectionality of gender and race. A highly recommended read for evidence based studies over a range of conditions and subject areas, you can hear Claude Steele talk about how he came to write the book, or watch a longer Claude Steele lecture.

Given the compelling number of studies demonstrating the awareness of stereotypes at an ever younger age, and the studies of older students showing real effect on subject choice and career path, it would be easy as someone who cares passionately about all children having as many doors open to them as possible to get disheartened and think “it will ever be thus”. However, if stereotypes are starting to take hold and influence choices at 6 and 7 then it is probably also a good time to intervene. Talking to some primary school teachers and children in year 3 and 4 i.e. ages 8-9 it is clear that it is possible at this age to intervene appropriately and reset stereotypes at least in the School environment. My 9 year-old can explain that “it used to be thought women weren’t intelligent enough to make decisions like voting but now we know that’s not true at all”. It is clear to me that we need to begin our work with much younger age groups than we work with traditionally.

And finally, we should perhaps try to convey that “brilliance” has several definitions. Yes, it can be defined as ” exceptionally clever or talented” but it can also mean “of light, radiant, blazing, beaming” . Now that might be something to aspire to for all of us.

Additional resources

Books:

Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do (Issues of Our Time) by Claude Steel (2011)

Pink Brain, Blue Brain: How Small Differences Grow Into Troublesome Gaps – And What We Can Do About It (2012) by Lise Eliot

Parenting Beyond Pink and Blue: How to Raise Your Kids Free of Gender Stereotypes, Christia Spears Brown (2014) Paperback

Ada Twist, Scientist and Rosie Revere, Engineer by Andrea Beatty and Dave Roberts

Videos and web links for resources:

How do we know it’s working? Book two tracking changes in pupils attitudes. A global citizenship toolkit by RISC, 2015 available from www.risc.org.uk/toolkit Fantastic classroom ideas covering diversity and equality alongside other global citizenship issues.

http://www.amightygirl.com/ Very good for links to books and facebook feed showcasing important women, many of them scientists and engineers.

http://www.ted.com/talks/colin_stokes_how_movies_teach_manhood?language=en

Research papers and similar:

Opening Doors, A guide to good practice in countering gender stereotyping in schools. Institute of Physics Report, October 2015

Gender stereotypes in Science Education Resources: A visual content analysis (2016) Kerkhoven, Russo, Land-Zandstra, Saxena and Rodenburg, PLOS ONE DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0165037

‘Not girly, not sexy, not glamorous’ primary school girls’ and parents’ reconstructions of science aspirations (2013) Archer, DeWitt, Osborne, Dillon, Willis and Wong, Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 21:1, 171-194, DOI:10.1080/14681366.2012.748676 ASPIRES project

“Balancing Acts”: Elementary School Girls’ Negotiations of Femininity, Acheivement and Science (2012) Archer, DeWitt, Osborne, Dillon, Willis and Wong, Science Education, 96, 967-989

STEAMing ahead

I have spent an inspiring couple of days at the Association for Science Education Conference held here at Reading, picking up ideas (and freebies) for my outreach work. A strong theme emerging across several sessions that I have attended is the potential for learning opportunities that could be gained by working across traditional “arts” and “science” boundary. The newest additional to my acronym dictionary is therefore STEAM, being Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics.

I have spent an inspiring couple of days at the Association for Science Education Conference held here at Reading, picking up ideas (and freebies) for my outreach work. A strong theme emerging across several sessions that I have attended is the potential for learning opportunities that could be gained by working across traditional “arts” and “science” boundary. The newest additional to my acronym dictionary is therefore STEAM, being Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics.

Two sessions were particularly inspiring. Carole Kenrick @Lab13_Gillespie described her time as a “scientist/inventor” in residence in a state primary school, running Lab_13. Amongst the many fantastic activities and initiatives she set up during this time which included helping with curriculum and staff CPD, supporting students to run a science committee and doing some original research with the students that reached the national press, Carole also started a STEAM club. She described how this had evolved from Science Club, to STEM club and finally to STEAM, entraining and enthusing more and more children and parents as it made the transition. By bringing creative arts and science together through, for example, designing robot costumes, backpacks, growing and producing their own plant-based dyes and then using these to make textiles, children who “didn’t like science” began to involve themselves in it, and “science geeks” found new creative talents and skills. Carole has written this up for teachwire and as a blog.

The second STEAM themed session I attended was a keynote lecture by Marcus du Sautoy on The Art of Mathematics and the Mathematics of Art. In a well attended and thought provoking lecture, he focused on particular examples where mathematics is linked, either knowingly or unknowingly, to arts. Firstly music, considering the work of Oliver Messiaen who used repeats of rhythm and chords with different prime numbers in each to great effect in the piece he wrote for a prisoner of war camp quartet, “Quatuor pour la fin du temps“ (“Quartet for the end of time”) . Also in music, I was intrigued to discover that Indian musicians appear to have been aware of the Fibonacci sequence way before Fibonacci – it describes the number of patterns you can make with successive numbers of quaver beats for example. ![]()

The connection between music and maths has often been made, but perhaps the other examples were less familiar. Firstly, in the visual arts, du Sautoy considered the success of Jackson Pollock paintings, attributed to them being fractals, and more than that, having similar fractal dimensions to those that we see in nature. This characteristic means that the level of complexity doesn’t change, no matter how much you “zoom in” to a Pollock painting, or in the natural world, trees. We also found out that to fake this you need to paint as a chaotic pendulum, one where the pivot moves as well as the pendulum. Apparently Pollock was able to do this through a natural combination of drunkenness and bad balance….

And finally to literature. The example used here was The Library of Babel by Jorge Luis Borges. Slightly different from the other examples, it is thought that this was a deliberate attempt by Borges to try to understand Poincare’s mathematics via literature. It  describes a library “that some call the universe” and discusses whether it is finite or not, some of the most challenging questions still being addressed in science today.

describes a library “that some call the universe” and discusses whether it is finite or not, some of the most challenging questions still being addressed in science today.

To my mind, science is already a creative subject. What could be more creative than dreaming up hypotheses, designing experiments, designing technology and equipment to deliver them and making visualisations of our data and results? Recent emphasis on novel visualisations of climate data for example have attracted much attention and featured in Olympic games opening ceremonies. But it is probably true that the majority of people beginning their science journey don’t see it this way. The explicit A in STEAM could help us to demonstrate that aspect and perhaps attract some new interest. It might also encourage the creative side in career scientists, although many of them already demonstrate this.

So, are you ready to put the A into STEM?

A significant revision to the climate impact of increasing concentrations of methane

Summary and Frequently Asked Questions relating to the paper:

Just when I thought it was safe to take a holiday, our paper presenting new detailed calculations of the radiative forcing for carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane was published in Geophysical Research Letters on 27th December. For me, this paper was a blast from the past, as one of the first papers I wrote as a postdoc in 1998 was on a similar topic, and shares 3 out of 4 authors, myself, Keith Shine and Gunnar Myhre.

The recent paper, co-authored with PhD student Maryam Etminan, describes new research on methane’s climate impact that has been performed at the Department of Meteorology at the University of Reading, UK and the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research – Oslo (CICERO) in Norway; it indicates that the climate effect of changes in methane concentrations due to human activity has been significantly underestimated. It also uses these detailed calculations to revise the simplified expressions for estimating radiative forcing adopted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The new calculations indicate that the direct effect of increases in the concentration of methane on climate is 25% higher than represented by the expressions previously adopted by the IPCC, making its present-day radiative forcing (relative to pre-industrial values) about one-third as powerful as carbon dioxide.

The paper has attracted some attention on social media as the calculations may have an impact on policy decisions in the future. Therefore I take the opportunity here, with much of the text below written by my co-author Keith Shine, to both summarise the study and answer some of the questions that have arisen so far.

Does this mean that our previous estimates of radiative forcing due to carbon dioxide have been over-estimated?

No. Carbon dioxide remains the most significant greenhouse gas driving human induced climate change.

In fact in this study we also looked at the estimates of forcing due to carbon dioxide using the same physical understanding as used for methane, and found forcing very similar to previous estimates, except for some underestimation at very high carbon dioxide concentrations.

So if the forcing due to methane has been underestimated in the past, why hasn’t the global mean temperature increased more?

The climate impact (e.g. temperature change) resulting from a radiative forcing change in the atmosphere depends on both the radiative forcing and how the climate system responds to that forcing. Although we have shown that the carbon dioxide forcings are little different to our earlier calculations, there are other changes that cause a radiative forcing that have documented very large uncertainties, for example aerosols (and in particular their impact on clouds) that could easily counteract the additional forcing from methane. Even if we knew the forcing accurately, the uncertainty in the climate response is also large enough that it isn’t a problem to reconcile the observed temperature changes. We are in fact refining the uncertainties through this type of study.

So why the focus on methane?

Human activity has led to more than a doubling of the atmospheric concentration of methane since the 18th century. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas. It is the second most important greenhouse gas driving human-induced climate change, after carbon dioxide. Its warming effect had been calculated to be about one-quarter of that due to carbon dioxide. Methane emissions due to human activity come from agricultural sources, such as livestock, soil management and rice production, and from the production and use of coal, oil and natural gas.

What did you do that was different?

Previous calculations had focused attention on the role of methane in the “greenhouse” trapping of infrared energy emitted by the Earth and its atmosphere, primarily at wavelengths of around 7.5 microns. The vital element in the new research is that detailed account is taken of the way methane absorbs infrared energy emitted by the Sun, at wavelengths between 1 and 4 microns.

The effect of this additional absorption of Sun’s infrared radiation is complicated, as it depends on the altitudes at which the additional energy is absorbed. This determines whether the extra absorption enhances or opposes the greenhouse trapping. It has been known for many years that the absorption of the Sun’s energy by carbon dioxide reduces its climate effect by about 4%, because much of the additional absorption happens high in the atmosphere.

The new calculations of the effect of methane indicate that much of the extra absorption is in the lower part of the atmosphere, where it has a warming effect. The research shows that clouds play a particularly important role in causing this enhanced warming effect. Clouds scatter some of the sun’s rays back into space; it is the additional absorption of these scattered rays by methane that drives the warming effect, a factor that had not been included in earlier studies.

Are these results important for climate change negotiations?

The new calculations are important for not only quantifying methane’s contribution to human-induced climate change, but also for the operation of the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). This takes into account emissions of many greenhouse gases in addition to carbon dioxide. The emissions of these other greenhouse gases are given a “carbon-dioxide equivalence” by multiplying them by a quantity called the “100-year Global Warming Potential” GWP(100); a similar approach is likely to be adopted by most countries for the operation of the UNFCCC’s more recent Paris Agreement.

The GWP(100) for methane includes not only its direct impact on the Earth’s energy budget, but methane’s indirect role, via chemical reactions, on the abundance of other atmospheric gases, such as ozone. Applying the results of the new calculations to the value of the GWP(100) presented in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) most recent (2013) assessment, enhances it by about 15%. This means that a 1-tonne emission of methane would be valued the same as 32 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions, up from the IPCC’s most recent value of 28. Hence for countries with large emissions of methane due to human activity, it would lead to a significant re-valuing of their climate effect, relative to emissions of carbon dioxide.

Can you be more specific about that?

In fact the GWP values have changed substantially due to new research since the Kyoto Protocol, and these changes are reported in the IPCC reports.

CO2 remains the dominant greenhouse gas emission from both developed (so-called Annex1) countries (77%) and non-Annex1 (65%) countries but using our revised value in place of the IPCC AR5 value, methane emissions now exceed 40% of CO2 emissions in developing countries, in CO2 equivalent terms, up from 36%. In developed countries, they are now almost one-quarter of the CO2 emissions (23% up from 20%).

So when might these new values influence policy?

The research team identified a number of uncertainties in the calculation of this enhanced absorption by methane, which will require further research to reduce. The new results are unlikely to be recommended for adoption in international treaties until they have been fully considered by the assessment process of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The new research was partly funded by the Research Council of Norway, and the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council.

The full paper is Radiative forcing of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide: A significant revision of the methane radiative forcing by M. Etminan, G. Myhre, E. J. Highwood, and K. P. Shine, Geophysical Research Letters, published online 27 December 2016, DOI: 10.1002/2016GL071930

It is open access and can be found at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2016GL071930/full

The IPCC working group 1 (2013) assessment report “Climate Change 2013, The Physical Science Basis can be found at https://ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1/

Balance or blend?

Life may not be a box of chocolates, but could it be a cup of tea?

The term “work-life” balance is much used and much-discussed. Many surveys and magazine articles discuss whether your “work-life balance” is as you want it to be. In our Athena SWAN applications (gender charter mark run by the Equality Challenge Unit) we are asked to discuss how the University is supporting “work-life balance”. Typically we talk about core hours, nursery care, and any family friendly policies we have.

However, many people object to the term “work-life balance” itself, and I can see why. Balance implies the two things are playing against each other… increase attention on one and the other must pay. How meaningful is it to imply that we are only alive outside of work? Many people are at least partially defined by the work that they do, or by their actions at work. Others are predominantly driven by the work that they do… and the term work-life balance somehow suggests that these people should “get a life”.

The alternative term work-life blend has been around for a while. The thinking behind the term is that in the modern world, with new technology etc, then for many people it is entirely possible to take care of some work things from home and some home things from work. Of course this isn’t possible for all roles… particularly those in the front line service industries, and manufacturing. The other reason for adopting this term is also that it removes the negative connotations of “balance”. With a “work-life blend” a much more diverse set of existences seems possible, all equally valid, and things are not in tension with one another in the same way (there are however only a limited number of hours in the day and therefore there must remain some tension!).

I have previously been rather resistant to the word “blend”. Perhaps it’s because I was thinking about it in terms of paint… if you mix lots of different paint colours together you inevitably end up with a murky mess that isn’t particularly enticing. I also worry that it means never being “off duty” from work, and I at least need to give my mind and body a change of scenery sometimes and find it hard enough to be properly “present” at times outside work as it is.

However, I might be changing my mind. Last night was our Edith Morley lecture given by Karen Blackett, OBE, CEO of media.com. She spoke about having “banned” the term “work-life balance” in her company, using instead, “work-life blend”. Uh-oh, I thought. I’m not sure I can buy that. But then Karen talked about having 6 well defined and non-negotiable strands to your blend, for example fulfilment at work, effective parenting, and such like, and using this to discuss your working practices with managers etc.

And this morning I thought of a new description for “blend” – a careful combination of different ingredients that are not subsumed by each other but together make up something delicious and supporting. In other words… my favorite English Breakfast tea!